A great Git commit

A good Git commit is not always easy to create, as it is more art than science in many aspects. While that sounds very flowery, it just means you, as the committer, need to exercise your judgement. That might sound nice, but some guidelines make life a lot easier, and ideally you do the same as your colleagues.

Of course this is not required at all: you can also just use Git as a snapshotting mechanism. But, in general it is nice to use tools to their fullest, so why should Git be any different?

Next time, we will look at why conventional commits are a waste of everybody’s time. But, first we must look at what good commits look like.

How big should a commit be?

While answers to this question vary, a popular convention is called atomic commits.11 Not to be confused with the identically named broader concept of atomic commits in computer science, for example, in database systems. Atomic commits are commits where each commit contains a single, complete unit of work. “Single” means the unit of work focuses on one logical change. The “complete” part name is more important: the commit should be complete on its own.

Of course, this still leaves a lot of wiggle room. When is a unit of work complete? I find a good rule of thumb to be asking if the commit would be mergeable on its own. This means the commit has no unfinished work (e.g. missing CSS styles or unimplemented functions), it includes passing tests, and all implemented parts work properly. Of course, this remains a judgement call. For example, if you are implementing a full-stack feature, you might have a set of changes for the frontend and another for the backend. These can be added in a single commit, but splitting them is also allowed, which means if the frontend changes were first, they will not work yet.

Another note is that a commit does not need to be useful. Sometimes, a commit can be extracting some code into a reusable function, without including a second usage of said new function.

For example, let us say we want to add an age field to some form in a web application. When we begin working on it, we notice that there is no number field in our framework yet, and that the validation logic for all fields is copied and pasted for each field type.

A series of atomic commits for this change might look like this:

$ git log --oneline

e4a5d6f (HEAD -> feature/number-field) Add age field to user form

c3b4a5d Add numerical field type

a2b3c4d Extract field validation into utilityThe earliest commit, a2b3c4d, extracts the duplicate validation code into a re-usable utility.

It is a complete unit of work, so it also contains tests for the new validation utility.

But it is also a single unit of work, so it does not include the new field type.

The second commit c3b4a5d adds a numeric field component.

This commit can, of course, use the new validation utility we added in the previous commit.

If there are UI tests, it also includes them.

But this commit does not add any uses of the new field type.

The final and most recent commit will then finally add the new field in the form where it was requested.

Note that there are other possibilities. For example, imagine the tests from the first commit revealed a bug. Do we then add a commit zero that fixes the bug? Do we let the tests fail in the first commit and fix the bug afterwards? Do we just fix the bug in the first commit? All these approaches have benefits and drawbacks.

In summary, the main benefits of using atomic commits are:

- Atomic commits make it easier to track regressions.

In the example above, if our refactor added a regression, the person investigating it later can clearly see it is a regression, since it was done in a refactor commit. Had we made one big commit, we might have to wonder if the regression was an intentional change for some cases we are not privy to. Similarly, things likegit bisectrely on this convention to work properly. - Atomic commits make it easier to manipulate them.

For example, if we forgot a field type in the refactor, we can easily amend the commit, create a fix-up commit, or interactively rebase the changes. - Atomic commits force you to do changes more deliberately.

This prevents changing a lot of things and places at the same time, which increases the risk that something is forgotten.

Atomic commits have been around a long time, even from before Git. Some useful resources on this are:

- Make Atomic Git Commits (2021), by Aleksandr Hovhannisyan.

- Atomic Commits to Version Control (2006), by Barney Boisvert.

- The Commit Guidelines from the Pro Git book by Scott Chacon and Ben Straub contain a section that you should “try to make each commit a logically separate changeset”.

- The contribution guidelines of many big projects suggest similar things, like those from Git itself.

Merging changes

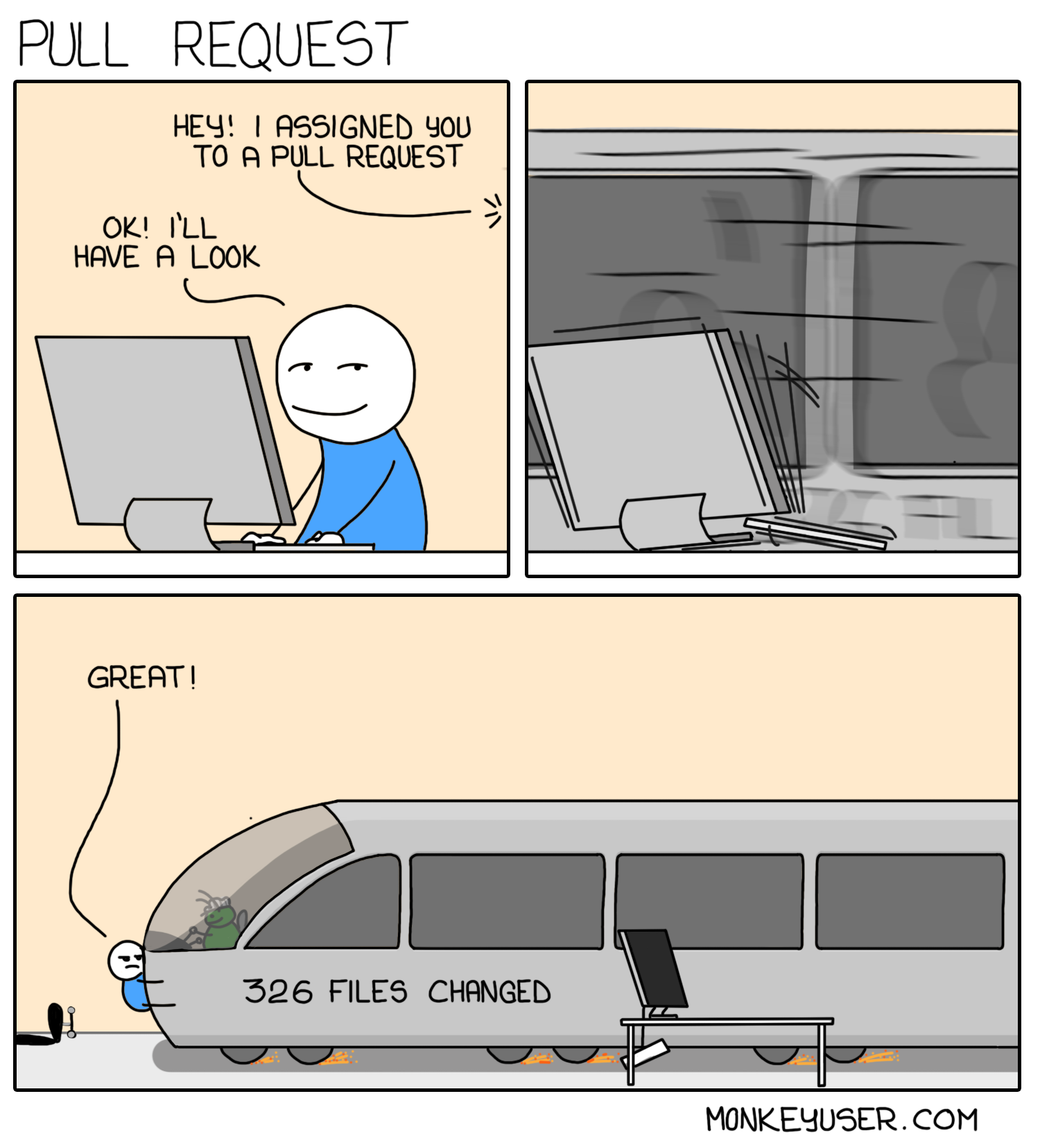

Assuming you are using branches, at some point you will need to merge your changes from your branch back into the master branch. On GitHub this is done via pull requests, on Gitlab via merge requests, and the Linux kernel works with patches via e-mail. Whatever it is called, the concept remains the same: a set of commits are proposed for inclusion into some branch. In teams, there is often a review of these changes before they are accepted.

There are various ways to merge commits into a branch, but the technical specifics are not important here. Our focus is the practice of squashing commits before merging. Normally, when merging, all commits end up in the destination branch one way or another.22 When rebasing these are technically new commits, but they are conceptually the same. With squashing, all commits from the branch are squashed into a single commit, which is then merged.

Squash merging is not without downsides, which are worse when practicing atomic commits.

Going back to the example above, if those three commits were squash merged, it would destroy the history of the carefully crafted commits you just created.

This has an impact on other tools as well, such as git blame or git rerere, which work less optimally without granular history.

A common counter-argument is that a pull request itself should be atomic_-ish_. The example above should have been split into three separate pull requests: one for the refactor, one for the framework improvement, and finally one for the new feature. Under this logic, squash merging is acceptable because the pull request contains only one logical change anyway.

Of course, everyone agrees that big refactors or enormous framework improvements should be done in separate pull requests. However, to implement squash merging well, this rule of atomic pull requests needs to be followed very strictly, or information is lost. Doing so introduces significant overhead for developers, especially if they want to “leave the code better than they found it” by introducing small improvements while in the area. This is a way of doing those small changes for which normally no time would be allocated.

Squash merging non-atomic pull requests, meaning pull requests with multiple atomic commits inside, is just information loss for no good reason. “But how will I cleanly see the history of pull requests?” Go look at the pull request page. “But now my history is littered with merge commits!” All good tools provide ways to hide those. “How will I know what pull request introduced commit X?” Use better tooling. If GitHub can show this information on the commit’s web page, so can your tooling calculate it.

There is one scenario in which squash merging might make sense: you do not have atomic commits. If a pull requests consist of a bunch of commits titled “WIP”, there is no value in keeping them. Squashing allows keeping a semblance of a clean history in this case. A better solution is to aim for atomic commits, and accept that some non-atomic commits might end up in the history. Git commits are free: having too many is seldom an issue.

For some reading on this, I recommend I hate squash merges by Matthias Beyer.

Naming a commit

Now that we have covered what goes into a commit, the next step is naming the commit, i.e. writing the commit message. This part is perhaps even more important than how big exactly a commit is. Using atomic commits is useless if the commits do not have a good description.

From the Pro Git book, we find the following commit message template:

Capitalized, short (50 chars or less) summary More detailed explanatory text, if necessary. Wrap it to about 72 characters or so. In some contexts, the first line is treated as the subject of an email and the rest of the text as the body. The blank line separating the summary from the body is critical (unless you omit the body entirely); tools like rebase will confuse you if you run the two together. Write your commit message in the imperative: "Fix bug" and not "Fixed bug" or "Fixes bug." This convention matches up with commit messages generated by commands like git merge and git revert. Further paragraphs come after blank lines. - Bullet points are okay, too - Typically a hyphen or asterisk is used for the bullet, followed by a single space, with blank lines in between, but conventions vary here - Use a hanging indent

We can distill this template and the other recommendation in the section Contributing to a Project into some rules:

- Separate the subject from the body with a blank line

- Limit the subject line to 50 characters

- Capitalize the subject line

- Do not end the subject line with a period

- Use the imperative form in the subject line

- Wrap the body at 72 characters

- Use the body to explain what and why vs. how

- Add metadata after the body, in the trailers

As with everything in this piece, this is not new information. For example, see How to Write a Git Commit Message by Chris Beams. Even the Pro Git book notes that it did not invent it, adapting it from A Note About Git Commit Messages by Tim Pope.

Subject line

The first five rules are about the subject line, which makes sense. The subject line is the most-read part of any commit, and is the only part shown in many commit lists (including tooling on the command line, but also on the web like on GitHub). You should assume the description will only be read by people actively looking into the history of a specific section of code.

Some of those rules are elementary: just follow them. For example, limit the subject line to 50 characters. Separate it with a blank line if a body or metadata follows it in the commit message. Do not write a period (or other punctuation in the rare cases those apply) at the end.

The most difficult one has to do with the content of the subject line: using the imperative form. The imperative form is the form used in sentences to give a command or instruction. Some examples are "Clean your room" or "Write this commit". Some examples of subject lines are then:

- Fix typo in documentation

- Refactor authentication code

- Enable database connection pooling

A good rule of thumb is to imagine your subject line in the sentence If applied, this commit will X, where X is your subject line:

- If applied, this commit will fix typo in documentation

- If applied, this commit will refactor authentication code

- If applied, this commit will enable database connection pooling

In addition to the imperative, many people employ a form of headlinese or telegraphic writing in the subject line. After all, just like in news headlines or telegrams, the subject line is severely restricted in length, so in many cases, “unnecessary” words are omitted by necessity. And when something is done frequently, it often becomes a defining characteristic, even if the underlying cause no longer warrants it. For this reason, many write like this in all commit message titles, even if there is enough space.

Description

Separated by an empty line from the subject line, the description of a commit is an optional part that gives more information. It is sometimes called the body of a commit, as an analogue to subjects and bodies in e-mail (quite possibly the inspiration for Git, since the creators of Git use a purely mail-based workflow).

While it is subject to rules 6 and 7, the requirements for the body of a commit are much more relaxed. While text should generally be wrapped at 72 characters, there can be valid reasons to deviate from this occasionally (just like in a plain-text e-mail). For example, if putting URLs in the body, there is no use in splitting a URL.

Secondly, the body should provide additional information about the changes in the commit, if necessary. This can include why the changes are made, why the original solution is no longer good, or even an explanation why the original code never worked. Remember, while the subject line is a general summary of the commit, the body is not. After all, the “how” of the changes is clear from the code itself; no need to repeat it in the body.

Consider, for example, the following commit and associated changes:

Update API timeout Body: Changed the DEFAULT_TIMEOUT constant from 5000 to 15000 in the configuration file.

diff --git a/src/config/constants.js b/src/config/constants.js

index 4a1b2c..9d8e7f 100644

--- a/src/config/constants.js

+++ b/src/config/constants.js

@@ -12,7 +12,7 @@ export const API_SETTINGS = {

RETRY_ATTEMPTS: 3,

// Timeout in milliseconds

- DEFAULT_TIMEOUT: 5000,

+ DEFAULT_TIMEOUT: 15000,

};First, the summary is pretty generic. Instead of saying “update”, we could say what we did: “increase” it. Second, the body is useless. Everyone can see what is written there by just looking at the changes in the commit.

Instead, the commit should look more like this:

Increase API timeout User analytics indicate a 12% failure rate on the purchase endpoint for mobile users in regions with high latency (specifically 3G networks). Based on our average latency logs, the new timeout covers 99.5% of current requests. This means failures will take longer to report to the user, but this is an acceptable trade-off to ensure order completion. Issue: #3467

Of course, this commit is exaggerated for educational effect. In reality, some explanation is useful, but there is also no need to duplicate the contents of the issue, especially if it is linked in the commit (see below).

Metadata or trailers

Finally, after the body, and again separated by an empty line, metadata about the commit can be added. For example, referencing the issue number the commit fixes, referencing a related commit, or even author related data.

Again, Git tools work with this as well.

For example, the git --signoff feature will add a Signed-off-by: XXX trailer to the commit message.

There is even a (lesser known) command git interpret-trailers to parse this information.

These are often very specific to a project and might not be useful to you at all.

Real-world example

As an example, let’s take an arbitrary commit from the Linux kernel, commit 8694138.

This is a simple commit, whose message in full is:

selftests: drv-net: wait for iperf client to stop sending

A few packets may still be sent out during the termination of iperf

processes. These late packets cause failures in rss_ctx.py when they

arrive on queues expected to be empty.

Example failure observed:

Check failed 2 != 0 traffic on inactive queues (context 1):

[0, 0, 1, 1, 386385, 397196, 0, 0, 0, 0, ...]

Check failed 4 != 0 traffic on inactive queues (context 2):

[0, 0, 0, 0, 2, 2, 247152, 253013, 0, 0, ...]

Check failed 2 != 0 traffic on inactive queues (context 3):

[0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 0, 1, 1, 282434, 283070, ...]

To avoid such failures, wait until all client sockets for the requested

port are either closed or in the TIME_WAIT state.

Fixes: 847aa55 ("selftests: drv-net: rss_ctx: factor out send traffic and check")

Signed-off-by: Nimrod Oren <noren@nvidia.com>

Reviewed-by: Gal Pressman <gal@nvidia.com>

Reviewed-by: Carolina Jubran <cjubran@nvidia.com>

Reviewed-by: Simon Horman <horms@kernel.org>

Link: https://patch.msgid.link/20250722122655.3194442-1-noren@nvidia.com

Signed-off-by: Jakub Kicinski <kuba@kernel.org>The three parts of the commit message are clearly visible:

- The subject line is a short summary of the changes

- The body contains why the changes are necessary

- The trailers contain various information required by the kernel development team

When not to do all these things

Crafting good commits and writing proper commit messages takes effort. Sadly, if some of the people working on the same project do not want to follow these conventions, a lot of the benefits become a lot less pronounced.

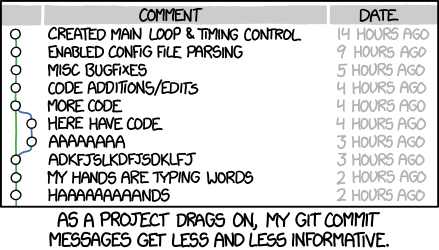

For example, if commits in your repository are just numbers or useless words for subsequent commits, it becomes much more difficult to effectively use the Git history.

Next time

Next time, we’ll look at conventional commits and why they go against a lot of the philosophy of Git, and are not even that useful.

Some images included on this page are licensed under the Attribution-NonCommercial 2.5 from https://xkcd.com/.